As the world celebrates Hip-Hop’s 50 anniversary, AllHipHop.com endeavors to explore all the ways that the culture has permeated different art forms outside of rap music.

The DNA of it is obvious … as obvious as the boombap of the music in one’s headphones.

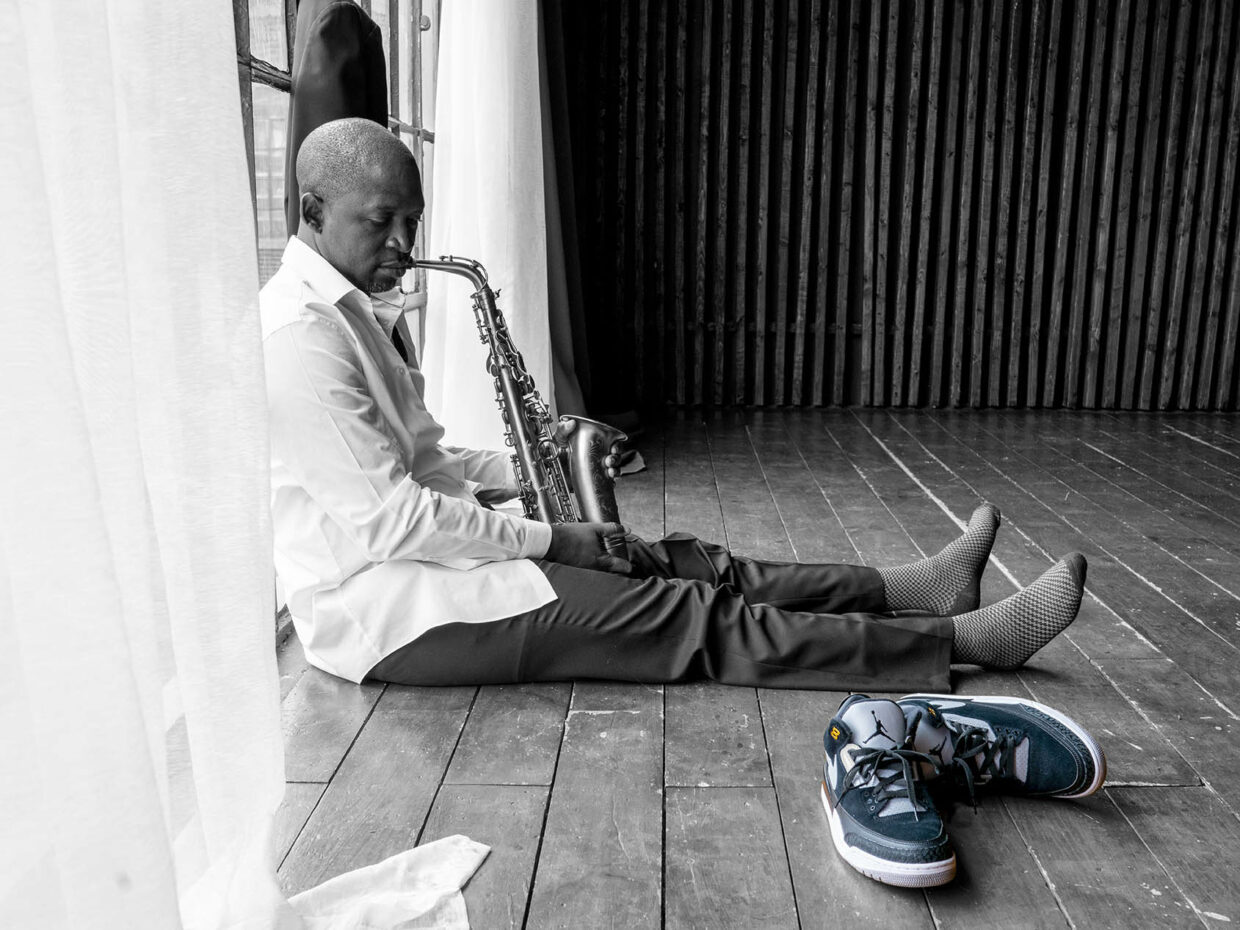

Just ask saxophone player Mike Phillips, the horn behind Hidden Beach’s epic Hip-Hop/ Jazz collab project “Unwrapped Vol. 4 and Vol. 5.” In an exclusive interview with Nikki Duncan-Smith, he discussed how he grew up in Money Earnin’ Mt. Vernon, during the height of the Golden Era of Hip-Hop and New Jack Swing, helped shape who he is as an artist, an aesthetic that made him a go-to for DJ D-Nice’s recent Club Quarantine event at Carnegie Hall.

AllHipHop: I’m a big fan of your hometown of “Money Earnin’” Mt. Vernon. So many Hip-Hop greats like Puffy, Heavy D, and Al B. Sure come from that side of town— the sixth borough.

Mike Phillips: Funny story about Al B. Sure. He’s been driving a candy-apple red BMW. And as kids, we’d be playing basketball. He’d stop at the corner and we would yell, “Al B. Sure.”

He would be there and we would just look at him and stare at this like iconic figure. He’d grab his phone and it would look like he is talking.

Me and Al, we’re good friends now. Once Al said, “I got a confession, man.

I was like, “What?” He continued, “Do you remember that most times when I used to see y’all when y’all was playing basketball in the park?” I was like “yeah.” He said, “My phone wasn’t on. It was $7 a minute. So, I would never have that phone on.” So, he used to be fronting, acting like he was on the phone. Years later he finally admitted it.

More than fronting, what Al and the rest of the Mt. Vernon’s success stories represented the aspirational lifestyle that could be obtained with hard work. According to Phillips, it was people like Al B. Sure and even the street dudes in the hood that encouraged him to play the saxophone. The street dudes were especially instrumental in his growth. They saw he had a gift and despite some of their choices, they knew he would be something great

How was it being a young person in the 80s in the 90s, with a saxophone walking through the hood?

It was different, but they had respect. They would be like, “Hey, that’s Mike. Leave him alone.”

I walked on my own everywhere.

I went to Washington elementary school. One day, I was playing Ms. Pac-Man and put my horn down. One of the kids took my horn. The principal got on the loudspeaker the next day and was like “Whoever took Mike Phillips’ horn got 24 hours to return it and I got it returned.”

So, I always felt protected and supported.

Phillips said he even was invited by the elders in the community to play his horn in the African drum circles, establishing for him that the gift he has did not belong to just one genre. He understood early that the spirit of his instrument could be represented in jazz, African and Hip-Hop. He pointed to Rakim as an example of how Hip-Hop and jazz are fused and many don’t even know it.

Rakim played sax in high school. So, when you hear those samples… when they’re in the studio … (he interpolates the horn section of “I Ain’t No Joke) … As a kid, I would just play along with it.

It was like five years ago when I found out that Rakim played the horn in high school that I put it all together. (He interpolated the horn from “Paid in Full”) He could have taken any part of the sample, but you took the one that had the flute … the woodwind.

He could have chopped up anything. But the fact that he was chopping up the music that was a part of his experience as a musician was part of why it was so powerful to me.

It was this combination of Hip-Hop and Jazz and the frustration of hearing derogatory messages in the music that led to the epic work with Hidden Beach.

I came out with a series called “Unwrapped” because I got tired of hearing B’s and H’s on records.

I got some of my friends and I said, “Why not play on these Hip-Hop beats?” It became one of the top-selling jazz records of the time. I was just playing off the Busta Rhymes beats.

After we put it out, I got an email from a father that said it was the first time he and his son sat down at the dinner table and listened to the same thing. That was powerful for me to bring two generations together.

The fact that they are experiencing it together made me feel so proud about being very intentional about things that Afrika Bambaataa to Kool Herc to Dexter Gordon to John Coltrane were doing and nothing not just I am bringing them together but that they belong together

Now, Phillips is taking all of this experience in a new role. Not just as the artist that set off the Carnegie Hall event with a powerful rendition of “Lift Every Voice” for the audience, but now as an executive. As of July 6, he has been named the Vice President of SRG Jazz, an independent label that focuses on legacy artists and their new works.

For Phillips, this is an opportunity to present jazz music in a way that the culture can digest it. Particularly after the success of young jazz musicians like Samara Joy captivating the national attention.

With his distinct perspective and deep cultural background, he appears to be the ideal individual to broaden the horizons of jazz and Hip-Hop.